(Where) is there humour in Old Testament narratives?

Helen Paynter writes:Micaiah: the lying prophet of God. Elisha: the grumpy old human who couldn't take a joke. The book of Kings has its fair share of surprises. What are they doing in this text? What is the reader supposed to learn from them? And should nosotros always stand up up and applaud the prophets wildly, whatever they get upwards to?

Helen Paynter writes:Micaiah: the lying prophet of God. Elisha: the grumpy old human who couldn't take a joke. The book of Kings has its fair share of surprises. What are they doing in this text? What is the reader supposed to learn from them? And should nosotros always stand up up and applaud the prophets wildly, whatever they get upwards to?

There are many humorous elements in Kings, all-time revealed by paying attention to the concluding formof the text; in other words, crediting the final editor with intelligence, subtlety and artistry, and considering in what means he has shaped the text to tell the story in the fashion that he intends.

Once Solomon'southward rule has been recounted, the majority of the combined volume of Kings is comprised of a series of 'regnal accounts', where a male monarch's reign is introduced with a standard formula, his deeds summarised with variable brevity, and then his decease and succession is described in standard terms. However, in the central part of the book, this pattern is disrupted by the appearance of Elijah and Elisha, performing an extraordinary array of miracles—and doing some rather unexpected and uncomfortable actions. This rather surprising interjection leads us to a number of unexplained 'issues' which Kings raises for us. For our purpose, the chief one is this: were the prophets righteous?

Elijah and Elisha have been held upwards equally heroes of religion for generations; that their actions are righteous is implicitly believed past many devout believers. Simply a more dispassionate consideration of some of their deportment may make the reader uncomfortable. Then, for case, in 2 Kings 1, Elijah calls downwards burn to consume 102 men, apparently on a whim; in 2 Kings 8, Elisha appears to send a simulated prophecy to Ben-Hadad and to incite Hazael to his murder; and maybe most strikingly of all, in 2 Kings ii, Elisha summons two bears to 'rip to pieces' 42 youths who have mocked him. These instances and others might lead us to ask the question of whether we are intended to approve of everything that a prophet of God does.

Calorie-free is shed on these questions if nosotros read the cardinal section of Kings with attention to the possibility of humour in the text. In particular, there are 2 unusual literary devices: carnivalisation and mirroring.

Carnivalisation

In medieval times, carnivals were held regularly in many societies, functioning to allow the periodic 'letting off' of steam. During a carnival, all normal rules and prohibitions were temporarily suspended. Normal social hierarchies were inverted (for case, the lord of the manor would serve his servants), behaviour was rowdy, drunken and bawdy, and the linguistic communication of the market identify prevailed.

This phenomenon was non confined to club, however. Following the work of Russian scholar Mikhail Bakhtin, it has been repeatedly shown that these same elements may invade literature, and produce a form of writing which is bawdy, norm-breaking and satirical. Typical elements of such carnivalised literature include the following:

- Unusual utilise of language: foreign-sounding speech, cursing, vulgarity, abusive speech

- Inversion of hierarchies: the making and unmaking of temporary 'kings' and 'queens'

- Foolery: the seeming simpleton who speaks truth to power

- Feasting: unusual, unexpected feasts

- Unusual expression of things that are vulgar, grotesque or offensive

- Baroque, unexpected breaches of normal cause and outcome

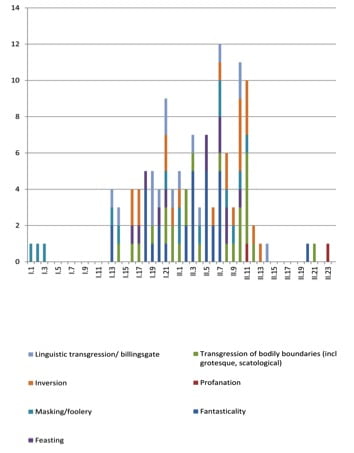

Examining Kings for features of carnivalisation reveals that the central department (1 Kings 13 to 2 Kings ten) in that location is an enormous number of them:

These capacity comprise the Elijah/ Elisha stories and the Aram/ State of israel narratives.

- Unusual apply of language. There are many instances of non-standard Hebrew in the cardinal section [[1]]. In particular, Elisha is characterised as having a strong northern emphasis. There are many insults and mockeries—some vulgar (e.g. ane Kings eighteen:27; 1 Kings 21:20-24; two Kings nine:22), some formulaic (e.g. ane Kings xx:10-xi). There are lies (due east.g. two Kings viii:x-14), people speak in quaint-sounding proverbs (1 Kings 20:10-11), and there are odd speech communication patterns (i Kings 18:ix-14).

- Inversion of hierarchies. Unexpected people take prominence. For example: the 'piffling daughter' of two Kings 5, whose wisdom exceeds that of the 'nifty man' Naaman; the lepers of 2 Kings vi:24-seven:20 who break a siege. Kings and queens are dramatically dethroned (1 Kings 22; 2 Kings nine:xxx-33).

- Foolery. Likely 'Fools', who deliberately or incidentally speak truth to power through simplicity, naïveté or other artistic means, include Micaiah (i Kings 22), the four lepers (2 Kings 6), and the disguised prophet (1 Kings 20:35-43).

- Feasting. There are a number of unusual 'feasts' in this text. Consider the king of Aram, who drinks so heavily that he loses the capacity to speak clearly (1 Kings 20:12-xviii); the feast of poisoned stew (ii Kings iv:38-41); the unexpected banquet celebrated betwixt enemies (two Kings half-dozen:22-23); the cannibalism of two mothers (2 Kings 6:28-29); and the grotesque feasting of Jehu inside the palace while dogs are eating Jezebel exterior (two Kings 9). Each of these feasts is in some manner unexpected. They should not accept been taking place at all, because it is an inappropriate (or surprising) time, an inappropriate bill of fare, or inappropriate company.

- Unusual expression of things that are vulgar, grotesque or offensive. There are many instances of this miracle, every bit indicated past the enormous bodycount in this part of Kings. But these are not simply battle deaths. They are described in florid and graphic ways. We have burnings, beheadings, cannibalism, human being sacrifice, animal mauling, crushings, mutilations and a stoning. Jezebel'due south body turns to dung on the plot at Jezreel (9:37) [[ii]]; her claret spatters the walls similar urine (9:33, c.f. 5.viii); at that place are seventy heads in baskets (x:7); the befouling of the temple of Baal becomes a latrine (ten:27).

- Bizarre, unexpected breaches of normal cause and consequence.In contrast to the sobriety of much of the remainder of Kings, the cardinal section abounds with boggling events. In detail, the Elijah-Elisha narratives are a compendium of florid phenomenon stories. Ii involve animals interim in unexpected means: ravens feed Elijah; bears respond to Elisha'southward curse by mauling 42 lads. Others are bizarre in other ways: a floating axe-head; oil and bread which mysteriously multiply; a fiery army that is sometimes visible and sometimes non, a mass auditory hallucination that causes an entire regular army to flee.

This clustering of features in the central part of Kings comprises literary carnivalisation. But what is the purpose of such a literary feature? In order to understand this, nosotros need to consider another literary device, the literary mirror.

Literary Mirroring

In William Shakespeare'due south drama Village, the royal courtroom hosts a play by travelling players. The story of this play is a brief retelling of Hamlet's own story—of betrayal and regicide. This is a literary mirror. By reflecting the large story within a pocket-sized sub-section of the work, it draws the audience's attention to, and comments on, the main narrative.

Literary mirrors can also function in a more fragmented way, with multiple petty glimpses of reflection scattered throughout the main narrative. The purpose of the mirror is to provide a sort of side-by-side commentary on the story. We can identify literary mirroring when we find repeated portions of text, similarity of names, or repetition of circumstances. There are a number of instances of such literary mirroring within Kings.

Mirroring of Elijah and Elisha and its effect

It is very clear to even the casual reader that the lives and ministries of Elijah and Elisha are very similar. Both raise from the dead an only child; both mysteriously multiply food; both office the river Jordan. However, there are a number of telling ways in which the two prophets are represented differently. In cursory: whereas Elijah goes everywhere at the command of the Lord, Elisha is described equally travelling entirely under his own volition; whereas Elijah e'er attributes his miracles to the power of the Lord, Elisha oft makes no reference to the Lord at all when he performs his miracles; in comparing with Elijah, Elisha appears very concerned with his own reputation (compare 1 Kings 18:36 with 2 Kings five:viii). So the characterisation of Elisha is far from beingness unequivocally positive.

Coupled with this, we have already noted the means in which carnivalisation has fabricated its manner into this text. This functions to cast doubt on authorisation, to subvert the powerful, to satirise the pompous, and to find ambiguity in the indubitable.

Then, when we read the story of Elijah, there is Elisha the Fool right backside him, coarsely aping him; mimicking his deeds, but introducing flaws in their functioning. Whereas Elijah oftentimes is noble and high-minded, Elisha tin can be ignoble and crass. But, in fact, his mirroring function is sophisticated and subtle; its effect is not to elevate one man of God at the expense of another. Neither Elisha nor Elijah is unambiguous; neither is 'proficient' or 'bad'; both are flawed. Elisha functions within the text as an internal commentary on his predecessor. He is similar the stand-up comedian who parrots the words of the politician with just enough subversion that we find ourselves laughing, non at the comedian, but with him at the directly man.

This brings us dorsum to the – at times – dubious ethical behave of the prophets. If the deportment of the prophets sometimes crusade the states embarrassment or moral discomfort, the discovery of carnivalisation encourages u.s.a. to trust this instinct. If Elisha seems bad-tempered when he summons the bears to maul the boys, this is because he isbad-tempered. No-1 is above criticism in the narrative, non fifty-fifty the men of God.

The world of Kings is a world of grand temples, ivory palaces and sweeping political manoeuvres. This is a world where the rich dominion and the poor serve them, where the 'goodies' are good and the 'baddies' are bad. Into this world comes the carnival, led by Elijah and Elisha. Not for them the role of dignified elder statesman, the role of leader of the opposition. Into the orderly, right-way-up world of State of israel and Judah, they innovate a cluttered, turbulent element, a rumbustious, playful chaos, where aught is as it seems, nothing is as you lot wait it to be. In this upside-down world, dauntless men are constitute to exist cowardly, men of God are revealed as egotists, enemies can become friends, and friends may stab you in the back. Here, bizarre things happen. Ravens may bring yous food, bears may attack unexpectedly, lions may seek you out and kill you. Here, axes float, and fires pause out all over the identify. Here, violent death is mutual and may take any number of forms. Yous might exist sacrificed by your father, beheaded with your brothers, eaten by your female parent, stoned on the orders of a queen, suffocated past your servant, or eaten past dogs. Yous canbe sure there will exist a great bargain of claret. This upside-down earth is not a earth of marble floors and ivory thrones, it is a world filled with the mutual stuff of everyday life, of cooking pots and oil and flour and wild herbs, of stews and bread, of lamps and beds and chairs. Here, kings may exist foolish or cowardly, and prophets may fail to hear the word of God. Not in this earth the grandiose speeches of the statesman or professional prayer-smith. Hither, people moan and grumble, exaggerate and whine, expletive and take oaths. Hither, anything might happen—and information technology probably will. In this world, little is certain, few can be trusted, and no-ane—peasant, king or prophet—is without fault or folly.

We must take care to note the places where the text is using humor to criticise the actions of even prophets. If we read with subtlety we are more likely to avoid the danger of attempting to defend the indefensible.

For more information, run across Paynter, H (2016). Reduced Laughter: Seriocomic Features and their Functions in the Volume of Kings. Leiden: Brill.

[one]Rendsburg, G. (1995) 'Linguistic Variation and the "Foreign Gene" in the Hebrew Bible', Israel Oriental Studies15: 177-190.

[ii]Carnivalisation in 2 Kings 9 and ten was previously identifies by Francesco García-Treto, (1990) 'The Fall of the House: A Carnivalesque Reading of 2 Kings 9 and x', JSOT46: 47-65.

Helen Paynter is Director of the Middle of the Report of the Bible and Violence, and Coordinator of Community Learning at Bristol Baptist College.

If yous enjoyed this, practice share information technology on social media, possibly using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is washed on a freelance basis. If you take valued this postal service, would you considerdonating £1.xx a month to back up the production of this blog?

If you lot enjoyed this, practice share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my folio on Facebook.

Much of my piece of work is done on a freelance ground. If you have valued this post, y'all can make a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Good comments that appoint with the content of the post, and share in respectful contend, can add real value. Seek first to sympathize, and so to be understood. Brand the most charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view debate as a conflict to win; address the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/where-is-there-humour-in-old-testament-narratives/

Publicar un comentario for "(Where) is there humour in Old Testament narratives?"